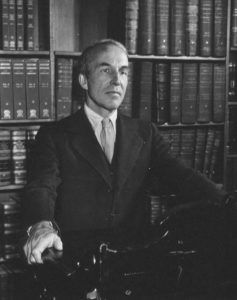

1960: The National Purpose-Archibald Macleish

- Wikipedia-de: Archibald MacLeish

„We Have Purpose – We All Know It“

ARCHIBALD MACLEISH

THAT SOMETHING HAS GONE WRONG IN AMERICA MOST OF US know. We are richer than any nation before us. We have more Things in our garages and kitchens and cellars than Louis Quatorze had in the whole of Versailles. We have come nearer to the suppression of grinding poverty than even the 19th Century Utopians thought seriously possible. We have wiped out many of the pests and scourges which afflicted humanity. We have lengthened men’s lives and protected their infancy. We have advanced science to the edges of the inexplicable and hoisted our technology to the sun itself We are in a state of growth and flux and change in which cities How out into countryside and countryside moves into cities and new industries are born and old industries vanish and the customs of generations alter and fathers speak different languages from their sons. In brief, we are prosperous, lively, successful, inventive, diligent-but, nevertheless and notwithstanding, something is wrong and we know it.

THAT SOMETHING HAS GONE WRONG IN AMERICA MOST OF US know. We are richer than any nation before us. We have more Things in our garages and kitchens and cellars than Louis Quatorze had in the whole of Versailles. We have come nearer to the suppression of grinding poverty than even the 19th Century Utopians thought seriously possible. We have wiped out many of the pests and scourges which afflicted humanity. We have lengthened men’s lives and protected their infancy. We have advanced science to the edges of the inexplicable and hoisted our technology to the sun itself We are in a state of growth and flux and change in which cities How out into countryside and countryside moves into cities and new industries are born and old industries vanish and the customs of generations alter and fathers speak different languages from their sons. In brief, we are prosperous, lively, successful, inventive, diligent-but, nevertheless and notwithstanding, something is wrong and we know it.

The trouble seems to be that we don’t feel right with ourselves or with the country. It isn’t only the Russians. We have outgrown the adolescent time when everything that was wrong with America was the fault of the Russians, and all we needed to do to be saved was to close the State Department and keep the Communists out of motion pictures. It isn’t just the Russians now: it’s ourselves. It’s the way we feel about ourselves as Americans. We feel that we’ve lost our way in the woods, that we don’t know where we are going-if anywhere.

I agree-but I still feel that the diagnosis is curious, for the fact is, of course, that we have a national purpose-the most precisely articulated national purpose in recorded history-and that we all know it. It is the purpose put into words by the most lucid mind of that most lucid century, the 18th, and adopted on the Fourth of July in 1776 as a declaration of the existence and national intent of a new nation.

Not only is it a famous statement of purpose: it is also an admirable statement of purpose. Prior to July 4, 1776, the national purpose of nations had been to dominate: to dominate at least their neighbors and rivals and, wherever possible, to dominate the world. The American national purpose was the opposite: to liberate from domination; to set men free.

All men, to Thomas Jefferson, were created equal. All men were endowed by their Creator with certain inlierable rights. Among these rights were life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. It was the existence of these rights which justified American independence from King George and justified also the revolution which would have to be fought for that independence. It was the existence of these rights which would provide a foundation for the govern rent to be established when independence was secure.

We not only have a national purpose: we have a national purpose of such aspiration, such potentiality, such power of hope that we refer to it-or used to-as the American Dream. We were dedicated from beginnings to the proposition that we existed not merely to exist but to be free, and the dedication was real in spite of the fact that it took us three generations and a bloody war to proctice our preachment within our own frontiers. It was real in spite of the fact that its practice is still a delusion in numerous pockets of hypocrisy across the nation.

To be free is not, perhaps, a political program in the modern sense, but from the point of view of a new nation it may be something better. The weakness of political programs-Five Year Plans and the like-is that they can be achieved. But human freedom can never be achieved be cause human freedom continuously evolving Condition. It is in finite in its possibilities_as in finite as the human soul which it enfranchises. The nation which seeks it and persists in its search will move through his tory as a ship moves on a compass course toward a constantly opening horizon.

And America did move steadily on be fore it lost head way in the generation in which we live. The extraordinary feel of liveness which the Americans communicated whether agreeably or not, to their early European visitors came from that sense of national expectation. We were never a very philosophical people politically after Jefferson and his contemporaries left us. We were practical men who took instruction from the things we saw and heard and did. But the purpose defined in our Declaration was a reality to us notwithstanding. It gave us aim as the continent gave us scope, and the old American character with its almost anarchic passion for idiosyncrasy and difference was the child of both. Those Missouri militiamen Parkman describes in The Oregon Trail slogging their way West to the war with Mexico, each in his own rig and each in his own way, could have constituted an army nowhere else. When, at Sacramento, a drunken officer commanded his company to halt and a private yelled „Charge!“ the company charged, knocking five times their number of Mexicans out of prepared entrenchments. The anarchy didn’t matter because, they were all headed in the same direction and the name of that direction was West-or freedom. They had a future in common and they had a purpose in common and the purpose was the enfranchise~ rent of men-of all men-to think for themselves, speak for themselves, govern themselves, pursue happiness for themselves and so become themselves.

Why then do we need to rediscover what our national purpose is? Because the words of the Declaration in its superb housing in the National Archives have become archival words, words out of history? Because the Bill of Rights of the American Constitution belongs, like the Magna Carta, in an airtight case? No one whp reads the newspapers could think SO. There has never been a time when courts and Congress devoted more of their attention to the constitutional guarantees of individual freedom than they do today, and as for the Declaration of Independence, its language is more alive in the middle of the 20th Century than it was in the middle of the 19th or even when it was written. It is not Communism, however Communism may attempt to exploit them, which has begotten the new nations of Asia and Africa or the new nationalistic stirrings in South America and the Caribbean and even in Europe. The Marxist dream is a dream of economic machinery, not of living men: of a universal order and system not a proliferation of nationalities. No, the dream which has set the jungle and the cane on fire is different and older. It is Thomas Jefferson’s dream_the dream which he and his contemporaries believed would change the world. It is changing the world-and not later than one might expect. Two hundred years is a short time in the history of institutions.

If the American Dream is out of date today it is out of date only in America-only in America and in the Communist countries in which the political police have extinguished it. But is it really out of date in America? Is its power to direct and draw us really so faint that we are lost in the blaze of our own prosperity and must enlist the aid of learned men to tell us where the future lies? That. I think, is a question for debate in these discussions.

Have we lost our sense of purpose or have we merely lost touch with it? Have we rejected the arduous labor to which our beginnings committed us? Or are we merely confused and bewildered by the volcanic upheavals which have changed the landscapes of our lives? Or is it neither rejection nor confusion? Is it nothing more than the flatulence and fat of an overfed people whose children pre pare at the milk-shake counter for coronary occlusions in middle age? Are we simply too thick through the middle of dream?

I doubt for myself that we have rejected the American Dream or have even thought of rejecting it. There are minorities, of course, who have little enthusiasm for the actualities of the American commitment to freedom, but this is largely because they do not understand what the struggle it culminated was all about. Certain areas on the

fringes of Europe were preserved by their geographical location from the necessity of living through the crisis of the Western mind which we call the Reformation, and American stock from these areas tends to [ind the master-mistress idea of the American Revolution-the idea which raised it from a minor war for independence to a world

event-incomprehensible if not actually misguided. It is not a question of religion. Catholics from the heart of the European continent understand Jefferson as well as any Protestant. It is a question of geography. Men and women whose ancestors were not obliged to fight the battle for or against freedom of conscience cannot for the life of them

understand why censorship should be considered evil or why authority is not preferable to freedom.

But all this does not add up to a rejection of the American dedication to liberty-the American dedication to the enfranchisement of the human spirit. The Irish Catholics, who are among the most persistent and politically powerful advocates of increasing censorship in the U.S., and who are brought up to submit to clerical authority in

matters which the American tradition reserves to the individual conscience, are nevertheless among the most fervent of American patriots. And if their enthusiasm for freedom of the mind is restrained, their passion for freedom of the man is glorious. Only if a separate system of education should be used to perpetuate the historical ignorance and moral obtuseness on which fear of freedom of the mind is based would the danger of the rejection of the American Dream from this quarter become serious. As for the rest the only wholehearted rejection comes from the Marxists with their curiously childish notion that it is more realistic and more intelligent to talk about economic machinery than about men. But the Marxists. both Mr. Hoovers to the contrary notwithstanding, have no perceptible influence on American opinion.

I cannot believe that we have rejected the purpose on which our Republic was founded. Neither can I believe that our present purposelessness results from our economic fat and our spiritual indolence. It is not because we are too comfortable that the dream has left us. It is true. I suppose, that we eat better-at least more-than any nation ever has. It is true too that there are streaks of American fat, some of it very ugly fat, and that it shows most unbecomingly at certain points in New York and Miami and along the California coast. But the whole country is not lost in a sluggish, sun-oiled sleep beneath a beach umbrella dreaming of More and More. We have our share, and more than our share, of mink coats and prestige cars and expense account restaurants and oil millionaires, but America is not made of such things as these. We are an affluent society but we are not affluent to the point of spiritual sloth.

Most American young women, almost regardless of income, work harder in their homes and with their children than their mothers or their grandmothers had to. For one thing, domestic servants have all but disappeared and no machine can cook a meal or mind a baby. For another, there are more babies than there have been for generations. For still another, the rising generation is better educated than its parents were and more concerned with the serious business of life-the life of the mind. To watch your daughter-in-law taking care of her own house, bringing up four children, running the Parent-Teacher Association, singing in the church choir and finding time nevertheless to read the books she wants to read and hear the music she wants to hear and see the plays she can afford to, is a salutary thing. She may think more about machines and gadgets than you ever did but that is largely because there are more machines and gadgets to think about. No one who has taught, as I have been doing for the past 10 years, can very seriously doubt that the generation on the way up is more intelligent than the generation now falling back. And as for the materialism about which we talk so much, it is worth remembering that the popular whipping boy of the moment among the intelligent young is precisely „Madison Avenue,“ that the mythical advertising copy writer who is supposed to persuade us to wallow in cosmetics and tail-Hn cars. We may be drowning in Things, but the best of our sons and daughters like it even less than we do.

What then has gone wrong? The answer, I submit, is fairly obvious and will be found where one would expect to find it: in the two great wars which have changed so much beside. The first world war altered not only our position in the world but our attitude toward ourselves and toward our business as a people. Having won a war to „make the world safe for democracy,“ we began to act as though democracy itself had been won-as though there was nothing left for us to do but enjoy ourselves: make money in the stock market, gin in the bathtub and whoopee in the streets. The American journey had been completed. The American goal was reached. We had emerged from the long trek westward to lind ourselves on the Plateau of Permanent Prosperity. We were there! It took the disaster of 1929 and the long depression which followed to knock the fantasy out of our heads but the damage had been done. We had lost touch with the diving force of our own history.

The effect of the second war was different-and the same. The second war estranged us from our genius as a people. We fought it because we realized that our dream of human liberty could not survive in the slave state Hitler was imposing on the world. We won it with no such ill sons as had plagued us 25 years before: there was another more voracious slave state behind Hitler’s. But though we did not repeat the folly of the ’20s we repeated the delusion of the ’20s. We acted again as though freedom were an accomplished fact. We no longer thought of it as safe but we made a comparable mistake: we thought of it as some thing which could be protected by building walls around it, by „containing“ its enemy

But the truth is. of course. that freedom is never an accomplished fact. It is always a process. Which is why the drafters of the Declaration spoke of the pursuit of happiness: they knew their Thucydides and therefore knew that the secret of happiness is freedom and the secret of freedom is courage.“ The only way freedom can be defended is

not by fencing it in but by enlarging it, exercising it. Though we did defend freedom by exercising it through the Marshall Plan in Europe, we did not, for understand able reasons involving the colonial holdings of our allies defend freedom by exercising it in Asia and Africa where the future is about to be decided.

The results have been hurtful to the world and to our selves. How hurtful they have been to the world we can see in Cuba where a needed and necessary and hopeful revolution against an insufferable dictatorship appears to have chosen the Russian solution of its economic difficulties rather than ours. We have tried to explain that ominous fact to ourselves in the schoolgirl vocabulary of the McCarthy years, saying that Castro and his friends are Communists. But whether they are or not-and the charge is at least unproved-there is no question whatever of the enormous popular support for their regime and for as much of their program as is now known. Not even those who see Communist conspiracies underneath everyone else’s bed have contended that the Cuban people were tricked or policed into their enthusiasm for their revolution. On the contrary the people appear to outrun the government in their eagerness for the new order. What this means is obvious. What this means is that the wave of the future, to the great majority of Cubans, is the Russian wave, not the American. That fact, and its implications for the rest of Latin America, to say nothing of Africa and Asia, is the fact we should be looking at, hard and long. If the Russian purpose seems more vigorous and more promising to the newly liberated peoples of the world than the American purpose, then we have indeed lost the „battle for men’s minds“ of which we talk so much.

As for ourselves, the hurt has been precisely the loss of a sense of national purpose. To engage, as we have over the past 15 years, in programs having as their end and aim not action to further a purpose of our own but counteraction to frustrate a purpose of the Russians is to invite just such a state of mind. A nation cannot be sure even of its own identity when it finds itself associated in country after country-as we have most recently in South Korea and Turkey-with regimes whose political practices are inirnical to its own.

What, then, is the issue in this debate? What is the problem? Not to discover our national purpose but to exercise it. Which means, ultimately, to exercise it for its own sake, not for the defeat of those who have a different purpose. There is all the difference in the world between strengthening the enemies of our enemies because they are against what we are against, and supporting the hopes of mankind because we too believe in them, because they are our hopes also. The fields of action in the two cases may be the same: Africa and Asia and Latin America. The tools of action-military assistance and above all economic and in dustrial and scientific aid-may look alike. But the actions will be wholly different. The first course of action surrenders initiative to the Russians and accepts the Russian hypothesis that Communism is the new force moving in the world. The second asserts what is palpably true, that the new force moving in the world is the force we set in motion, the force which gave us, almost two centuries ago our liberating mission. The first is costly, as we know. The second will be more costly still. But the second, because it recaptures for the cause of freedom the initiative which belongs to it and restores to the country the confidence it has lost, is capable of succeeding. The first, because it can never be anything but a policy of resistance, can only containe to resist and to accomplish nothing more. There are those, I know, who will reply that the liberation of humanity, the freedom of man and mind, is nothing but a dream. They are right. It is. It is the American dream.