1974: CIA-Cult Intelligence: INTRODUCTION by Anthony Lewis Victor Marchetti and John D. Marks : The CIA and the Cult of Intelligence

INTRODUCTION by Anthony Lewis

Few books change national attitudes. This one did. When it was first published in 1974, the Central Intelligence Agency was regarded by most Americans who had heard of it as an unusually skillful, wise, and successful branch of the United States Government. The CIA and the Cult of Intelligence began a process of public reappraisal-a process that continued through newspaper reports, the work of a presidential commission , and congressional hearings. Over the years the tide of opinion ebbed and flowed; the CIA lost and then regained much of its political support . But there was a lasting change in attitudes, I think: bringing a degree of skepticism toward the agency. an unwillingness to let it continue enjoying a total exemption from the scrutiny to which the Constitution generally makes government subject. What Victor Marchetti and John Marks did was a classic vindication of the American constitutional theory that public knowledge is essential to both democratic and effective government. Not just the First Amendment but the whole system constructed at the Philadelphia convention in 1787 rests on the premise of an informed electorate , holding its rulers accountable and thus preventing the corruption of power. As Justice Brandeis put it a century and a half later: „Sunshine is the best of disinf’ectants.“ Marchetti and Marks let light in on the work of the CIA. They supplied facts where there had been none.

It is difficult, years later, to remember our state of permissive ignorance concerning the CIA. I do not exclude myself – or most journalists. We thought of the agency as better informed than the State or Defense departments, and rather more on the liberal side in international affairs. We knew men who worked out in Langley; they were notably well-bred, articulate, perhaps a bit bookish–certainly not the sort of people to conspire against freely elected governments or plot the assassination of Left Wing leaders. That faith survived the Bay of Pigs intact. For the most part it even survived the Vietnam War, which shattered the general postwar love affair between the Washington press corps and the government, as the press learned that officials did not know more and could not be trusted to advance shared values.

Marchetti and Marks showed us that the Central Intelligence Agency. too. had made mistakes: not just slips or human errors but grave errors of policy. They made us aware . dramatically. that the agency not only engaged in classic intelligence work-the collecting of information by one means or another-but also intervened in the political process of other countries by covert actions: subsidies to favored parties, dirty tricks, the supply of arms. They also corrected a general belief that the CIA concentrated its efforts on the Soviet Union. In fact, they said, „The agency works mainly in the Third World,“ in relatively small and weak countries-and there , „at least since 1961, the CIA has lost many more battles than it has won, even by its own standards.“

In that paragraph of their manuscript, Marchetti and Marks listed African, Asian, and Latin American countries that had been the targets of CIA coven intervention. But it is only now, years afterward, that we are able to read some of the names. The list was struck out by CIA censors in 1973, and the courts upheld the censorship. Further administrative ‚ appeals finally resulted in permission to publish these countries from the original list: Chile, the Congo, Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, the Philippines. (See p. 320.) How fast the world moves: since the original censorship, the Congo has changed its name to Zaire, Chile has been taken over by a military junta, and Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam have all come under the control of what was in 1972 the Communist regime of North Vietnam.

There is a great irony attached to The CIA and the Cult of lmelligence. The book was censored, and the legal theory adopted by the courts to justify that censorship was in my judgment the most dangerous defeat in many years for Americans‘ freedom to speak and write and read without official approval. Yet despite the censorship, Marchetti and Marks reached the public with their facts and their criticism of governmental conduct, just as the Constitution intended. Indeed , in a fascinating way, the heavy hand of the CIA censors and of the courts actually helped them to get their message across: the CIA helped to destroy its own myth of wisdom and efficiency.

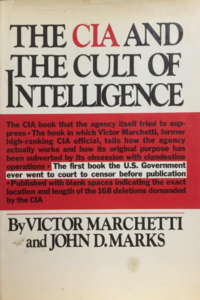

The way it happened was this: CIA officials read the manuscript in 1973 and told Marchetti and Marks that they had to remove 339 passages. nearly a fifth of the book . The officials may have thought that the authors or the publisher. Alfred A . Knopf. would lose interest and drop the whole idea. They did not. First Marchetti and Marks and their lawyer-Melvin L. Wulf. then legal director of the American Civil Liberties Union-argued each of the deletions with the agency. Some of them were manifestly absurd: the fact, for example. that Richard Helms of the CIA. at a National Security Council meeting. had mispronounced the name of the Malagasy Republic. Many others were facts long since published: not secrets at all. After long negotiations the CIA yielded on 171 items, not out of kindness but because officials knew that every deletion was going to be contested in court and they did not want to look foolish. That left 168 censored passages. And then Knopf decided to go ahead and publish the book with blanks for those passages, and with the sections that the CIA had originally cut but then restored printed in boldface .

The result was a dramatic demonstration of how censorship works: the arbitrariness, the design very often to prevent official embarrassment rather than protect real secrets. The book had special impact. And some people who mattered noticed how far the CIA had gone to stop disclosure of its blunders. abuses of power. and mistaken policies. I think it is fair to say that the doubts raised then led in time to the investigative reports by Seymour Hersh of The New York Times, the Rockefeller Commission, and the Senate Intelligence Committee under Senator Frank Church of Idaho.

The legal device by which the CIA was able to see the manuscript in the first place , and censor it, was an ingenious one. Victor Marchetti had been an official of the agency and. like other employees, had signed a promise not to disclose secrets he had learned there, while on the job or later. These secrecy agreements had always been considered a way of alerting CIA employees to their responsibility and of putting moral pressure on them, and of course they could be fired for breaking the promise. But the agreements were not thought to be legally binding; in fact, Wil liam Colby, later Director of Central Intelligence , told a congressional committee that the agency had no way to get a court to stop leaks. Then . when the CIA officials learned that Marchetti was planning to write a book, they went into court and claimed that his agreement was a legally binding „contract ,“ enforceable by an injunction against Marchetti . The courts so held. and they subjected Victor Marchetti to an order unique in American history. For the rest of his life , he was forbidden to disclose „in any manner“-wriling, conversation , whatever-any classified information that he had learned while at the CIA. unless he got official clearance first.

As I write. eight years later, that order still stands. And over the years the CIA has enforced it with what could be called niggling rigor. Agency representatives have let Marchetti know they were in the audience at meetings he was to address, so he had better not say anything out of line. Once, on Canadian radio. he referred to a CIA experiment in wiring cats with minimicrophones; the government complained that he had violated the injunction.

What makes all this so extraordinary, legally , is that the First Amendment frowns on „prior restraints“: orders, like the one against Marchetti, that prevent someone from writing or speaking except on terms approved by authorities. The First Amendment says that Congress shall make no law „abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press.“ In the great case of Near v. Minnesota, in 1931, the Supreme Court said that the „chief purpose“ of those words had been to make sure this country would not have a system of prior censorship like the one that had existed in seventeenth century England , when nothing could be printed without an official license. How, then , can the courts have applied just such a system to Victor Marchetti (and , as co-author of this book, John Marks)? The answer is hard to find as one reads the opinions; judges have not faced the problem squarely. But their logic seems to be that Marchetti, and others who work for the CIA, waive their First Amendment rights when they take the job and sign the secrecy agreement. Even if it were that easy to give up one’s constitutional rights-and the courts have usually said that it is not-there would still be another problem. It has been the rule in this country that officials cannot impose regulations unless Congress authorizes them, and especially not when constitutional rights are involved. Thus in 1959 the Supreme Court said the Defense Department could not use a security system thai relied on anonymous accusers because Congress and the President had not clearly authorized such a system . Yet Congress had never considered, much less approved. the theory of censorship by „contract“ imposed on Marchetti and Marks.

Melvin L. Wulf. in his introduction to the original edition of this book . describes how the case dc:veloped–how the government advanced and the courts approved the sweeping theory of Secrecy by Contract . To that account I can add one or two observations from a different perspective .

First , it is necessary to say a word about „sc:crets.“ Even in the United States. the most open of countries, the average citizen still tends to be impressed when a government official talks about „secrets“ or “classified information.“ And of course there are real secrets. which deserve protection: codes, for instance . or the plans for nuclear retaliation to an enemy attack . But the overwhelming proportion of the millions of documents classified by federal officials are routine affairs of no real security interest. That fact . known to anyone who deals regularly with the Washington bureaucracy, is beautifully demonstrated by this book itself. Consider these items that the CIA originally tried to censor and then allowed to be published in the original edition :

• „The Chilean election was scheduled for the following September. and Allende, a declared Marxist, was one of the principal candidates.“ (See p. 12.)

• „Henry Kissinger, the single most powerful man at the forty-committee meeting on Chile.“ (See p. IS.)

• „As incredible as it may seem in retrospect , some of the CI A’s economic analysts (and many other officials in Washington) were in the early 1960s still inclined to accept much of Peking’s propaganda as to the success of Mao’s economic experiment.“ (See p. 103.) This new edition provides further evidence of the foolishness so often covered by claims that a disclosure would threaten the national security. It includes twenty-five passages censored when the book was originally published but released after years of further administrative proceedings. Looking at these supposed „secrets,“ the reader is bound to wonder about the good faith of the CIA censors, or their common sense.

One of these newly published items is about a chemical that makes mud more slippery. The CIA thought of dropping it on the Ho Chi Minh Trail during the rainy season, hoping to interrupt the Vietnamese supply route. (See p. 107.) The idea didn’t work. and it was all over before 1974, but the censors still kept it out.

Another passage now published said that the Soviets had electronic bugs in the American embassy code room in Moscow-and were able to translate the sounds of typewriters into letters. (See p. 186.) The bugs had long since been found, the leak ended. The Russians knew what they had been doing. From whom was it being kept a secret?

Most bewildering of all is a series of censored items about Africa. The book describes a meeting of the National Seurity Council under President Nixon in December 1969. After the first sentence the censors cut out a passage. Now restored (p. 248) . it reads: „The purpose of this session was to decide what American policy should be toward the governments of southern Africa.“

A few lines down, the censors cut in midsentence: „There was sharp disagreement within the government on how hard a line the United States should take with the . . . “ Restored, it goes on: “ . . . white-minority regimes of South Africa, Rhodesia, and the Portuguese colonies in Africa. “ Then two words were cut from this sentence: „Henry Kissinger talked about the kind of general posture the United States could maintain toward the —— and outlined the specific policy options open to the President.“ The missing words turn out to be: „white regimes.“

Finally, the censors cut a reference to the fact that Kissinger had sent a National Security Study Memorandum (NSSM 39) to depanments interested in southern Africa. NSSM 39 was in fact published and widely discussed in 1974. It took the view that the various movements for majority rule in southern Africa were unlikely to succeed soon .

To the extent that those censored passages on Africa point anywhere, it is toward a discussion of policy. The Kissinger-Nixon policy was founded on the belief that the Portuguese would hold on to their African colonies indefinitely. Within a few years that premise was shattered, and the whole policy had to be reappraised. Is there any serious argument of security that the American public should not have been allowed, five years afterward, to reflect on the wisdom of the policy and the way it was made? What has it got to do with CIA „secrets“?

Second, there is a misconception that the legal theory developed in the Marchetti case allows the CIA to suppress something by an ex-employee only if the agency can convince the courts of a genuine threat to security. This was the belief, amazingly, of a twenty-six-year CIA veteran, Cord Meyer, who wrote a book about his career. He had trouble clearing it through the agency censors, spending a lot of time and money to prove that material once classiFied had long since become public. Then Meyer wrote a newspaper column about his troubles, saying that the censors even tried to delete „whole sections of a chapter describing how a typical KGB station operates abroad,“ even though that could hardly be a secret to the KGB. But he concluded that what he called „peacetime censorship“ was not too dangerous. for this reason:

Fortunately. the Federal courts have held that it is not sufficient for the government to prove that information has been stamped ··secret.“ The burden of proof is on the government to demonstrate that release of the information could cause damage to the national security .

Unfortunately, Meyer’s statement is the opposite of the truth. In the Marchetti case , the courts held precisely that they would not weigh the possible damage of any censored passage to the national security; it was enough if the CIA could show simply that something had been included in a document stamped SECRET while Marchetti was in the agency and had not been officially released since. That was the unhappy end of the judicial process that was still under way when Melvin L. Wulf wrote his introduction.

He sounded a note of hope because , at that point, he had had a favorable decision from conservative Federal Judge Albert V. Bryan, Jr. , of Alexandria, Virginia. Judge Bryan heard the testimony of high CIA officials to the effect that the 168 passages they wanted to delete were classified-and in most cases did not believe what they said. He found that only 27 of the 168 contained material that had been specifically classified while Marchetti was in the agency. But on appeal the government swept all that away. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit held that Judge Bryan had imposed too high a standard on the CIA in demanding specific proof of classification. It was enough if the item in question had appeared in a classified document, even an entire book stamped SECRET; there was no need to show that the classifying officer had had the particular matter in mind . Nor was there any need for the agency to convince the court that the national security was at risk. CIA officials, the court said, were entitled to a „presumption of regularity.“ In short, the courts simply should not second-guess or even examine the Cl A’s reasons for censoring an exemployee’s words: there will be no meaningful judicial review. And that leads to a third observation. Judges are evidently uneasy about mixing in the intelligence business. Only that can explain the extraordinary deference paid to the CIA in this and other cases.

Five years after Victor Marchetti. John Marks. and their publisher were defeated in the courts, the Supreme Court took an even more radical and dangerous step toward official censorship. The case was that of Frank Snepp, who had been a CIA man in Vietnam and wrote a book, Decent /ruerval. about the last days of the American presence there. Snepp felt that high officials, notably Secretary of State Kissinger, had made craven and immoral decisions, worst of all in abandoning thousands of Vietnamese colleagues to their fate. He did not submit his manuscript for clearance, as he had promised to do in his secrecy agreement, but published the book before the agency was aware of his plans.

Too late to get an injunction against Snepp, the Justice Department a�ked the courts to make some new and even more ingenious law, imposing a massive financial penalty on Snepp for violating his ··contract . “ Summarily-without hearing argument or even allowing Sncpp’s lawyers to brief the issue-the Supreme Court imposed a „constructive trust“ on Snepp. requiring him to give the government everything he earned from his book. That was $140,000,Snepp’s sole income over a period of three years, with nothing deductible even for his living expenses. (The sum was less. incidentally, than he would have earned by staying in the CIA and keeping quiet about the wrongs he had observed.)

In the Marchetti case the lower courts developed the idea of Secrecy by Contract-the theory that, without congressional authorization, the CIA could make its employees sign away their constitutional rights for the rest of their lives. In the Snepp case the Supreme Court seemed to remove even the requirement of a contract from this theory. It hinted that anyone in the government who had access to important secrets could be sued for violating his „trust“ if he published something without clearance. whether or !’lot he had signed a secrecy agreement. The Court put it: „Quite apart from the plain language of the [secrecy] agreement. the nature of Snepp’s duties and his conceded access to confidential sources and materials could establish a trust relationship.“ That approach would in effect give the United States the equivalent of Britain’s notorious Official Secrets Act , which makes it a crime to disclose any government information-however innQCuous-without official approval .

There was a revealing indication o f judicial attitudes i n the Supreme Court’s opinion in the Snepp case , a footnote that read as follows:

Every major nation in the world has an intelligence service. Whatever fairly may be said about some of its past activities. the CIA (or its predecessor the OSS) is an agency thought by every President since Franklin D. Roo!>evelt to be essential to the security of the United States and-in a sense-the free world. It is impossible for a government wisely to make critical decisions about foreign policy and national defense without the benefit of dependable foreign intelligence. Sec generally T. Powers, The Man Who Kept the Secrets.

The reverential tone of that footnote shows again that the courts give the CIA a discretion that they would not think of allowing any other agency of government-not even the President of the United States, to judge by the Nixon Tapes Case. The cult of intelligence thrives on the bench. It has only to be added that the justices evidently did not know what they were doing when they cited the Thomas Powers book. It contained large amounts of classified information, disclosed by various past and present CIA officials when interviewed by Powers.

The political branches have responded more realistically than the courts to the problem of preventing the CIA abuses of power. The process that this book helped to start ended with permanent House and Senate Intelligence committees doing a continuing job of scrutiny, and with the Executive Branch keeping a much more formal check on the agency. But the legal precedent set by the treatment of The CIA and the Cult of Jmelligence has not become any less dangerous with time. In that sense. the book is a classic piece of evidence in the endless war for freedom of speech and of the press. In the old days. in this country. the test of that freedom was the right of the soapbox orator or the radical editor to expound his theory of society. Today the issue is not freedom to propagate ideas but freedom to tell the facts about government-and freedom of the citizen to acquire the facts. As government becomes more powerful in our lives the ability to know what it is doing and hence to control its power becomes ever more important. We can still hope that some day a less deferential Supreme Court will apply that truth to the exercise of secret power, holding even the Central Intelligence Agency subject to the Constitution, and will \indicate The CIA and rhe Culr of /nrel/igence in law as it has long smce been \indicated in the necessary truths it told .

Impressum