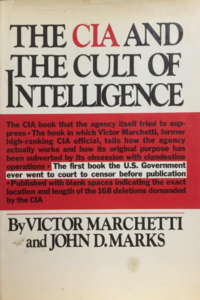

1974: CIA-Cult Intelligence:AUTHORS' PREFACES Victor Marchetti and John D. Marks : The CIA and the Cult of Intelligence

AUTHORS‘ PREFACES – I

My introduction to the intelligence business came during the early years of the Cold War, while serving with the U.S. Army in Germany. There , in 1952. I was sent to the European Command’s „special’· school at Oberammergau to study

Russian and the rudiments of intelligence methods and techniques. Afterward I was assigned to duty on the East German border. The information we collected on the enemy’s plans and activities was of little significance, but the duty was good, sometimes even exciting. We believed that we were keeping the world free for democracy, that we were in the first line of defense against the spread of communism.

After leaving the military service , I returned to college at Penn State. where I majored in Soviet studies and history. Shortly before graduation , I was secretly recruited by the CIA, which I officially joined in September 1955; the struggle between democracy and communism seemed more important than ever, the CIA was in the forefront of that vital international battle. I wanted to contribute.

Except for one year with the Clandestine Services. spent largely in training. most of my career with the CIA was devoted to analytical work. As a Soviet military specialist, I did research, then current intelligence. and finally national estimates-at the time, the highest form of intelligence production. I was at one point the CIA’s–and probably the U.S. government“s–leading expert on Soviet military aid to the countries of the Third World. I was involved in uncovering Moscow’s furtive efforts that culminated in the Cuban missile crisis of 1962 and. later, in unraveling the enigma of the „Soviet ABM problem. „

From 1966to 1969 I served as a staff officer in the Office of the Director of the Cl A. where I held such positions as special assistant to the Chief of Planning. Programming. and Budgeting. special assistant to the Executive Director, and executive assistant to the Deputy Director. It was during these years that I came to see how the highly compartmentalized organization performed as a whole, and what its full role in the U.S. intelligence community was. The view from the Office of the Director was both enlightening and discouraging. The CIA did not, as advertised to the public and the Congress, function primarily as a central clearinghouse and producer of national intelligence for the government. Its basic mission was that of clandestine operations, particularly covert actionthe secret intervention in the internal affairs of other nations. Nor was the Director of CIA a dominant–or much interested-figure in the direction and management of the intelligence community which he supposedly headed. Rather, his chief concern , like that of most of his predecessors and the agency’s current Director, was in o\·erseeing the CIA’s clandestine activities.

Disenchanted and disagreeing with many of the agency’s policies and practices, and, for that matter, with those of the intelligence community and the U . S. government, I resigned from the CIA in late 1969. But having been thoroughly indoctrinated with the theology of „national security“ for so many years, I was unable at first to speak out publicly. And, I must admit. I was still imbued with the mystique of the agency and the intelligence business in general. even retaining a certain affection for both. I therefore sought to put forth my thoughts-perhaps more accurately. my feelings-in fictional form. I wrote a novel, The Rope-Dancer, in which I tried to describe for the reader what life was actually like in a secret agency such as the Cl A , and what the differences were between myth and reality in this overly romanticized profession.

The publication of the novel accomplished two things. It brought me in touch with numerous people outside the inbred, insulated world of intelligence who were concerned over the constantly increasing size and role of intelligence in our government. And this, in turn, convinced me to work toward bringing about an open review and, I hoped, some reform in the U.S. intelligence system. Realizing that the CIA and the intelligence community are incapable of reforming themselves, and that Presidents, who see the system as a private asset, have no desire to change it in any basic way, I hoped to win support for a comprehensive review in Congress. I soon learned, however, that those members of Congress who possessed the power to institute reforms had no interest in doing so. The others either lacked the wherewithal to accomplish any significant changes or were apathetic. I therefore decided to write a book-this book-expressing my views on the CIA and explaining the reasons why I believe the time has come for the U.S. intelligence community to be reviewed and reformed.

The CIA and the government have fought long and hardand not always ethically-first to discourage the writing of this book and then to prevent its publication. They have managed, through legal technicalities and by raising the specter of „national security“ violations, to achieve an unprecedented abridgment of my constitutional right to free speech. They have secured an unwarranted and outrageous permanent injunction against me. requiring that anything I write or say, „facwal, fictional or otherwise,“ on the subject of intelligence must first be censored by the CIA. Under risk of criminal contempt of court , I can speak only at my own peril and must allow the CIA thirty days to review, and excise, my writings-prior to submitting them to a publisher for consideration.

It has been said that among the dangers faced by a democratic society in fighting totalitarian systems, such as fascism and communism, is that the democratic government runs the risk of imitating its enemies‘ methods and, thereby, destroying the very democracy that it is seeking to defend. I cannot help wondering if my government is more concerned with defending our democratic system or more intent upon imitating the methods of totalitarian regimes in order to maintain its already inordinate power over the American people.

VICTOR MARCHETTI

Oakton , Virginia

February 1974

AUTHORS‘ PREFACES – II

Unlike Victor Marcheni , I did not join the government to do intelligence work . Rather, fresh out of college in 1966, I entered the Foreign Service. My first assignment was to have been London, but with my draft board pressing for my services, the State Department advised me that the best way to stay out of uniform was to go to Vietnam as a civilian advisor in the so-called pacification program. I reluctantly agreed and spent the next eighteen months there , returning to Washington just after the Tet offensive in February 1968. From personal observation . I knew that American policy in Vietnam was ineffective . but I had been one of those who thought that if only better tactics were used the United States could „win .“ Once back in this country. I soon came to see that American involvement in Indochina was not only ineffective but totally wrong.

The State Department had assigned me to the Bureau of Intelligence and Research. first as an analyst of French and Belgian affairs and then as staff assistant to State’s intelligence director. Since this bureau carries on State’s liaison with the rest of the intelligence community. I was for the first time introduced to the whole worldwide network of American spying-not so much as a participant but as a shuffler of top-secret papers and a note-taker at top-level intelligence meetings. Here I found the same kind of waste and inefficiency I had come to know in Vietnam and , even worse, the same sort of reasoning that had led the country into Vietnam in the fir.;t place. In the high councils of the intelligence community, there was no sense that intervention in the internal affairs of other countries was not the inherent right of the United States. „Don’t be an idealist; you have to live in the ‚real‘ world .“ said the professionals. I found it increasingly difficult to agree .

For me. the last straw was the American invasion of Cambodia in April 1970. I felt personally concerned because only two months earlier. on temporary assignment to a White House study group. I had helped write a relatively pessimistic report about the situation in Vietnam. It seemed now that our honest conclusions about the tenuous position of the Thieu government had been used in some small way to justify the overt expansion of the war into a new country.

I wish now that I had walked out of the State Department the day the troops went into Cambodia. Within a few months, however, I found a new job as executive assistant to Senator Clifford Case of New Jersey. Knowing of the Senator’s opposition to the war, I looked at my new work as a chance to try to change what I knew was wrong in the way the United States conducts its foreign policy.

During my three years with Senator Case, when we were concentrating our efforts on legislation to end the war, to limit the intelligence community, and to curb presidential abuses of executive agreements, I came to know Victor Marchetti. With our common experience and interest in intelligence, we talked frequently about how things could be improved. In the fall of 1972. obviously disturbed by the legal action the government had taken against the book he intended to write but which he had not yet started, he felt he needed someone to assist him in his work . Best of all would be a coauthor with the background to make a substantive contribution as well as to help in the actual writing. This book is the result of our joint effort.

I entered the proJect in the hope that what we have to say will have some effect in influencing the public and the Congress to institute meaningful control over American intelligence and to end the type of intervention abroad which, in addition to being counterproductive , is inconsistent with the ideals by which our country is supposed to govern itself. Whether such a hope was misguided remains to be seen.

JOHN D. MARKS

Washington. D.C.

February 1974

Impressum